Finch Telecommunications, Inc. (Early Newspaper Fax Delivery)

- Guaranteed authentic document

- Orders over $75 ship FREE to U. S. addresses

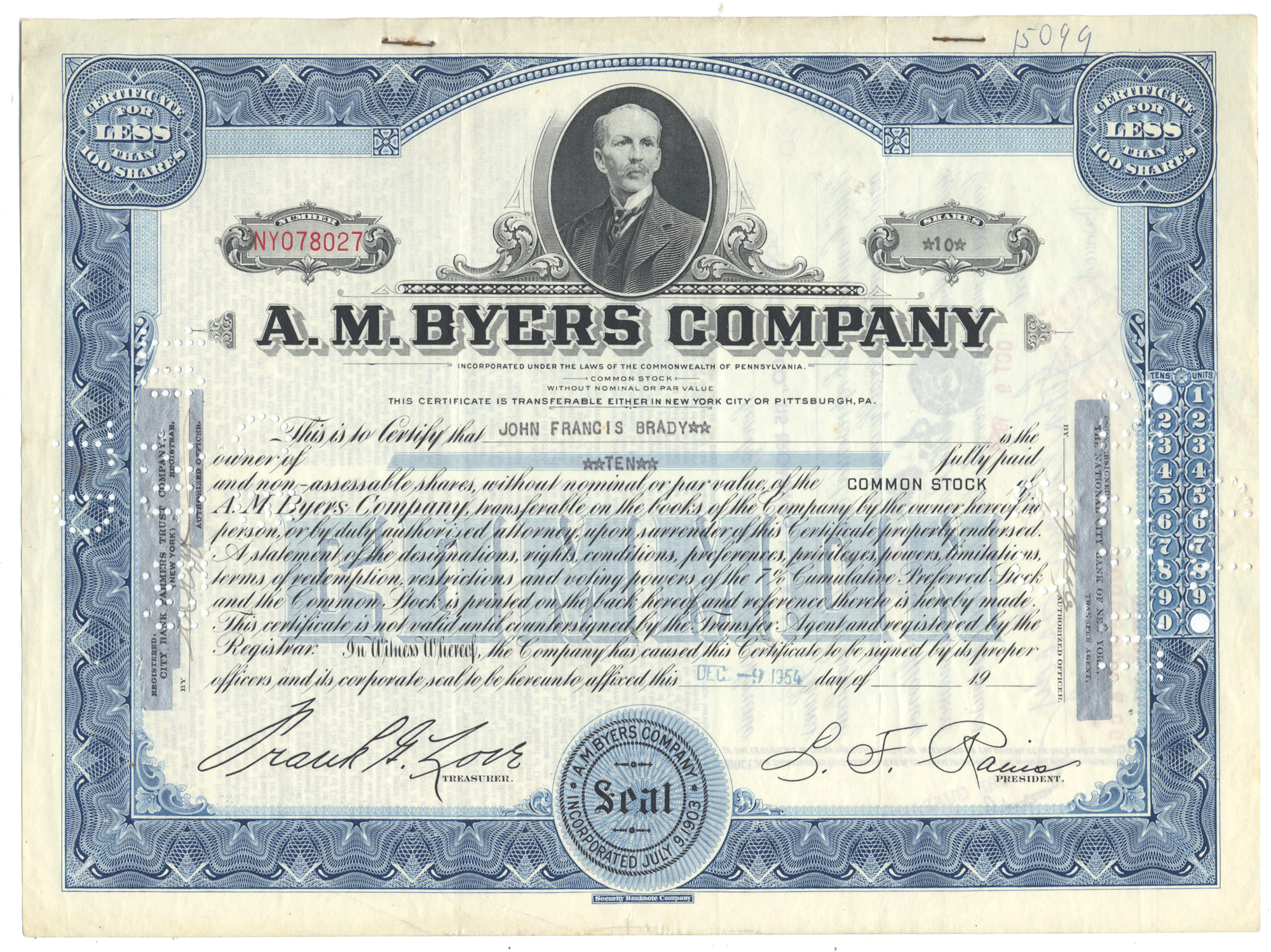

Product Details

CompanyFinch Telecommunications, Inc.

Certificate Type

Capital Stock

Date Issued

Specimen, circa 1930's

Canceled

Yes

Printer

Hamilton Bank Note Company

Signatures

Machine printed

Approximate Size

12" (w) by 8" (h)

Images

Show the exact certificate you will receive

Guaranteed Authentic

Yes

Additional Details

NA

Historical Context

In the early 1930s, radio facsimile looked like the dream application for newspapers. They could use their own local radio stations to deliver newspapers directly to consumers during overnight hours. It would eliminate the cost of printing and distribution and shift those costs onto consumers, who would provide their own printers and paper.

This led several radio stations and newspapers to experiment with facsimile transmission during the late 1930s.

The person most responsible for this technology was William G. H. Finch. He worked for the International News Service and set up their first teletype circuits between New York, Chicago and Havana. He became interested in facsimile machines and eventually amassed hundreds of patents.

In 1935, he established Finch Telecommunications Laboratories to build and market his system. Although RCA had already developed a facsimile system, it was only focused on its commercial possibilities. Finch envisioned the delivery of newspapers to the public via radio facsimile.

The Finch system circumvented RCA’s patents in several ways.

First, image details were transmitted by varying the amplitude of an audio tone, instead of its frequency.

Second, it recreated the image by generating an electric current at the tip of a stylus to trace the image onto thermally sensitive paper (the origins of the thermal paper still used by cash registers today). Synchronization between the transmitter and receiver used the 60 Hz line frequency. The Finch scanning head focused a pinpoint scanning spot on the document. A motor moved the scanner across the page while another motor advanced the page at the end of each scanning line. Low-frequency sync pulses were inserted at the end of each line. The result was an audio signal that could be fed into any conventional AM transmitter.

Finch receivers sold for $125 and were housed in a one-foot-square wooden box that could be connected to the speaker of any radio receiver. The images were drawn onto a continuous roll of thermal paper 5 inches wide that sold for one dollar and would last about a week. The process was slow, taking about 20 minutes to print a 12-inch page, but a timer was used to capture the transmissions from a local AM station during overnight hours. Six hours overnight was enough time to print a six-page, two-column news bulletin.

Several stations received FCC permission in 1937 and 1938 to experiment with the Finch system. The first was KSTP in St. Paul, Minn. It was followed by WHO in Des Moines, Iowa; WGH in Newport News, Va.; WOR in New York; WGN in Chicago; WHK in Cleveland; WSM in Nashville, Tenn.; and WWJ in Detroit.

McClatchy Newspapers published the Radio Bee over KFBK in Sacramento and KMJ in Fresno, Calif. It required a staff of seven to produce the radio newspaper, and McClatchy bought 100 Finch receivers to distribute to listeners.

Most radio facsimile transmissions shifted from the AM band to the ultrahigh frequencies in the early 1940's. About a dozen of these experimental stations were built, including the Milwaukee Journal station WTMJ, which transmitted over W9XAF.

Nonetheless, it soon became clear that radio facsimile was a technological dead end.

Despite all the promotion and hype, the public had neither asked for, nor cared about, the technology.

Receivers were expensive, suffered from frequent paper jams and outages, and were subject to content loss due to static.

To make matters worse, there were two incompatible standards (RCA and Finch) fighting for market dominance.

Further, advertisers didn’t want to risk their money on the new medium, preferring the safety of traditional media.

The World War II paper shortages caused most facsimile stations to cease operations, and when the war was over, it was all but forgotten in the rush to build the new television industry. An attempt to bring it back on the FM band found no takers.

William Finch’s company went into bankruptcy in 1952, and RCA eventually took over many of his patents. Finch died in Florida in 1990 at the age of 93.

Related Collections

Additional Information

Certificates carry no value on any of today's financial indexes and no transfer of ownership is implied. All items offered are collectible in nature only. So, you can frame them, but you can't cash them in!

All of our pieces are original - we do not sell reproductions. If you ever find out that one of our pieces is not authentic, you may return it for a full refund of the purchase price and any associated shipping charges.