Louisville and Northern Railway and Lighting Company (Signed by Samuel Insull)

- Guaranteed authentic document

- Orders over $100 ship FREE to U. S. addresses

Product Details

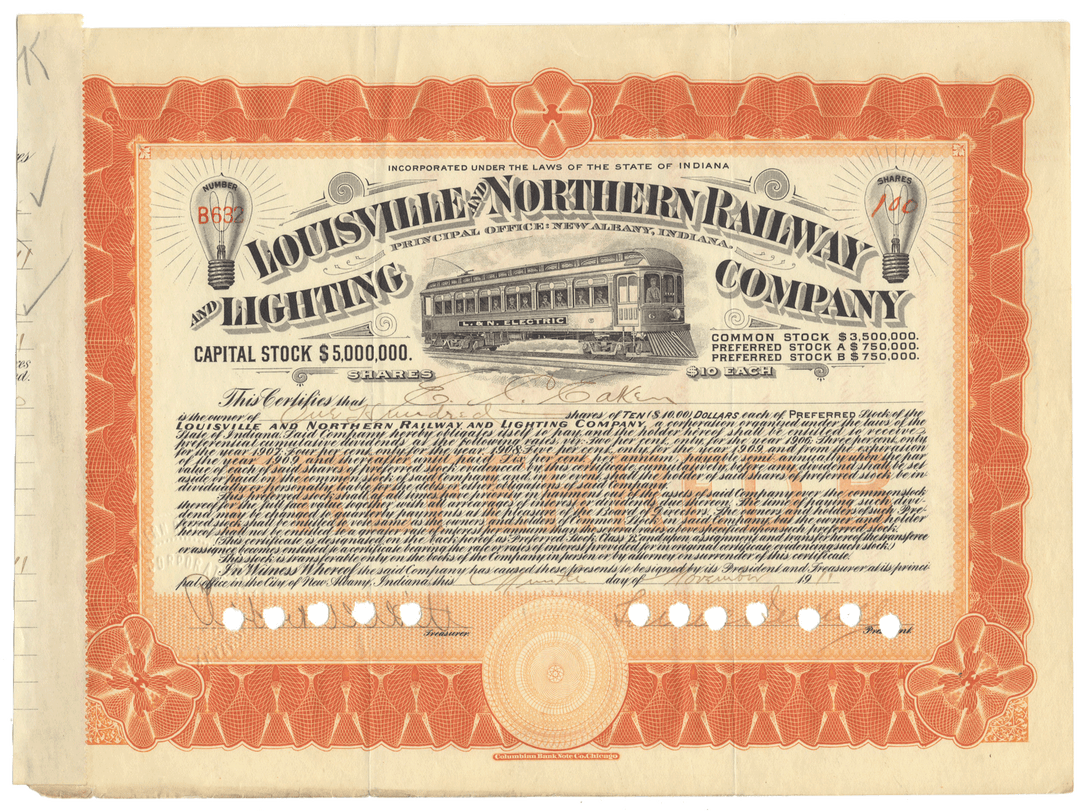

Nicely engraved antique stock certificate from the Louisville and Northern Railway and Lighting Company dating back to the 1910's. This document, which is signed by the company President (Samuel Insull) and Treasurer, was printed by the Columbian Bank Note Company, and measures approximately 11" (w) by 8" (h).

This certificate's vignette features a detailed view of one of the company's trolley cars. Light bulbs house the certificate number and share amount.

Images

You will receive the exact certificate pictured.

Historical Context

Samuel Insull began construction of the Louisville and Southern Indiana Traction Company line to Indianapolis from Louisville in 1903. Insull’s Louisville and Northern Railway Lighting Company controlled the line starting in 1905. Insull acquired the Indianapolis, Columbus and Southern Traction Company in 1912 and organized the Interstate Public Service Company that same year.

Samuel Insull

In 1881, at the age of 21, Samuel Insull emigrated to the US, complete with side whiskers to make him appear older than his years. In the decade that followed, Insull took on increasing responsibilities in Edison's business endeavors, building electrical power stations throughout the US. With several other Edison Pioneers, he founded Edison General Electric, which later became the publicly held company now known as General Electric. Insull rose to become vice-president of General Electric in 1889, but was unhappy at not being named its president. When the presidency went to someone else, Insull moved to Chicago as head of the Chicago Edison Company. Another consideration is that he was caught between opposing factions when J. P. Morgan combined the Thomson-Houston Electric Company and Edison General Electric to form the new company in April 1892. Those loyal to Edison accused Insull of selling out, and in fact he did welcome the infusion of capital from Vanderbilt, J. P. Morgan, and others as necessary for the company's future development. Edison quickly forgave him, but others did not, and it seemed a good idea to get out of town.

Life in Chicago

The Western Edison Light Co. was founded in Chicago in 1882, three years after Edison developed a practical light bulb. In 1887, Western Edison became the Chicago Edison Co. Insull left General Electric and moved to Chicago in 1892, where he became president of Chicago Edison that year. Chicago Edison was struggling, losing money, until Insull discovered a way to make it profitable during a Christmas visit to Brighton, England in 1894. To his surprise, he saw that the shops were closed, but every light in them was burning; something that never happened in the US. Finding the head of the town's electric company, he asked him how this could happen and was told the secret to it was not a flat rate bill, but use of a demand metered billing system, measuring not only total power consumption, but a set of rates for low-demand and high-demand electric use times. By 1897, Insull had worked out his formulas enough to offer Chicago electric customers two-tiered electric rates. With the new system, many homeowners found their bills lowered by 32 percent within a year.

In 1897, he incorporated another electric utility, the Commonwealth Electric Light & Power Co. In 1907, Insull's two companies formally merged to create the Commonwealth Edison Co. As more people became connected to the electric grid, Insull's company, which had an exclusive franchise from the city, grew steadily. By 1920, when it used more than two million tons of coal annually, the company's 6,000 employees served about 500,000 customers; annual revenues reached nearly $40 million. During the 1920s, its largest generating stations included one on Fisk Street and West 22nd and one on Crawford Avenue and the Sanitary Canal.

Insull began purchasing portions of the utility infrastructure of the city. When it became clear that Westinghouse's support of alternating current was to win out over Edison's direct current, Insull switched his support to AC in the War of Currents

His Chicago area holdings came to include what is now Federal Signal Corporation, Commonwealth Edison, Peoples Gas, and the Northern Indiana Public Service Company, and held shares of many more utilities. Insull also owned significant portions of many railroads, mainly electric interurban lines, including the Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad, Chicago Rapid Transit Company, Chicago Aurora and Elgin Railroad, Gary Railways, and Chicago South Shore and South Bend Railroad. He helped modernize these railroads and others.

As a result of owning these diverse companies, Insull is credited with being one of the early proponents for regulation of industry. He saw that federal and state regulation would recognize electric utilities as natural monopolies, allowing them to grow with little competition and to sell electricity to broader segments of the market. He used economies of scale to overcome market barriers by cheaply producing electricity with large steam turbines, such as the installations in the 1929 State Line Generating Plant in Hammond, Indiana. This made it easier to put electricity into homes.

Samuel Insull also had interests in broadcasting. Through his long association with Chicago's Civic Opera, he thought the new medium of radio broadcasting would be a way to bring opera performances into people's homes. On hearing of the work of Westinghouse to establish a radio station in Chicago, he contacted the company. Together the two companies arranged for a radio station to be built in Chicago which would be operated jointly by Commonwealth Edison and Westinghouse. KYW's first home was the roof of the Edison Company building at 72 West Adams Street in Chicago, and it went on the air November 11, 1921. It was Chicago's first radio station.

Though the partnership came to an end in 1926, with Westinghouse buying out Edison's interest in KYW, Insull's interest in broadcasting did not stop there. He formed the Great Lakes Broadcasting Company in 1927 and purchased Chicago radio stations WENR and WBCN; the two stations were merged on June 1, 1927, with Insull paying a million dollars for WENR alone. Insull moved the stations first into the Strauss Building, then into Insull's Civic Opera House, where WENR became an affiliate of the NBC Blue Network. Insull's Great Lakes Broadcasting Company also included a mechanical television station, W9XR, which began in 1929 after the company installed the first 50,000 watt radio transmitter in Chicago for its two radio stations.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and ensuing Great Depression, caused the collapse of Insull's public utility holding company empire.

When Insull's fortune started to fade, he sold both WENR and WBCN along with W9XR, to the National Broadcasting Company in March 1931. Two years after its purchase of the radio stations and the mechanical television station, NBC shut W9XR just as it had done with W9XAP, which came with its purchase of WMAQ (AM).

Great Depression

Insull controlled an empire of $500 million with only $27 million in equity. (Due to the highly leveraged structure of Insull's holdings, he is sometimes wrongly credited with the invention of the holding company.) His holding company collapsed during the Great Depression, wiping out the life savings of 600,000 shareholders. This led to the enactment of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935.

Insull fled the country initially to France. When the United States asked French authorities that he be extradited, Insull moved on to Greece, where there was not yet an extradition treaty with the US. He was later arrested and extradited back to the United States by Turkey in 1934 to face federal prosecution on mail fraud and antitrust charges. He was defended by famous Chicago lawyer Floyd Thompson and found not guilty on all counts.

Death

In July 1938, the Insulls visited Paris to see the Bastille Day festivities. Insull suffered from a heart ailment, and his wife Gladys had asked him not to take the Métro because it was bad for his heart. Nevertheless, Insull had made frequent declarations that he was "now a poor man" and on July 16, 1938, he descended a long flight of stairs at the Place de la Concorde station. He died of a heart attack just as he stepped toward the ticket taker. He had 30 francs—84 cents—in his pocket at the time and was identified by a hotel laundry bill in his pocket. Insull was receiving an annual pension totaling $21,000 from three of his former companies when he died. Insull was buried near his parents on July 23, 1938, in Putney Vale Cemetery, London, the city of his birth. His estate was found to be worth about $1,000 and his debts totaled $14,000,000, according to his will.

Additional Information

Certificates carry no value on any of today's financial indexes and no transfer of ownership is implied. All items offered are collectible in nature only. So, you can frame them, but you can't cash them in!

All of our pieces are original - we do not sell reproductions. If you ever find out that one of our pieces is not authentic, you may return it for a full refund of the purchase price and any associated shipping charges.