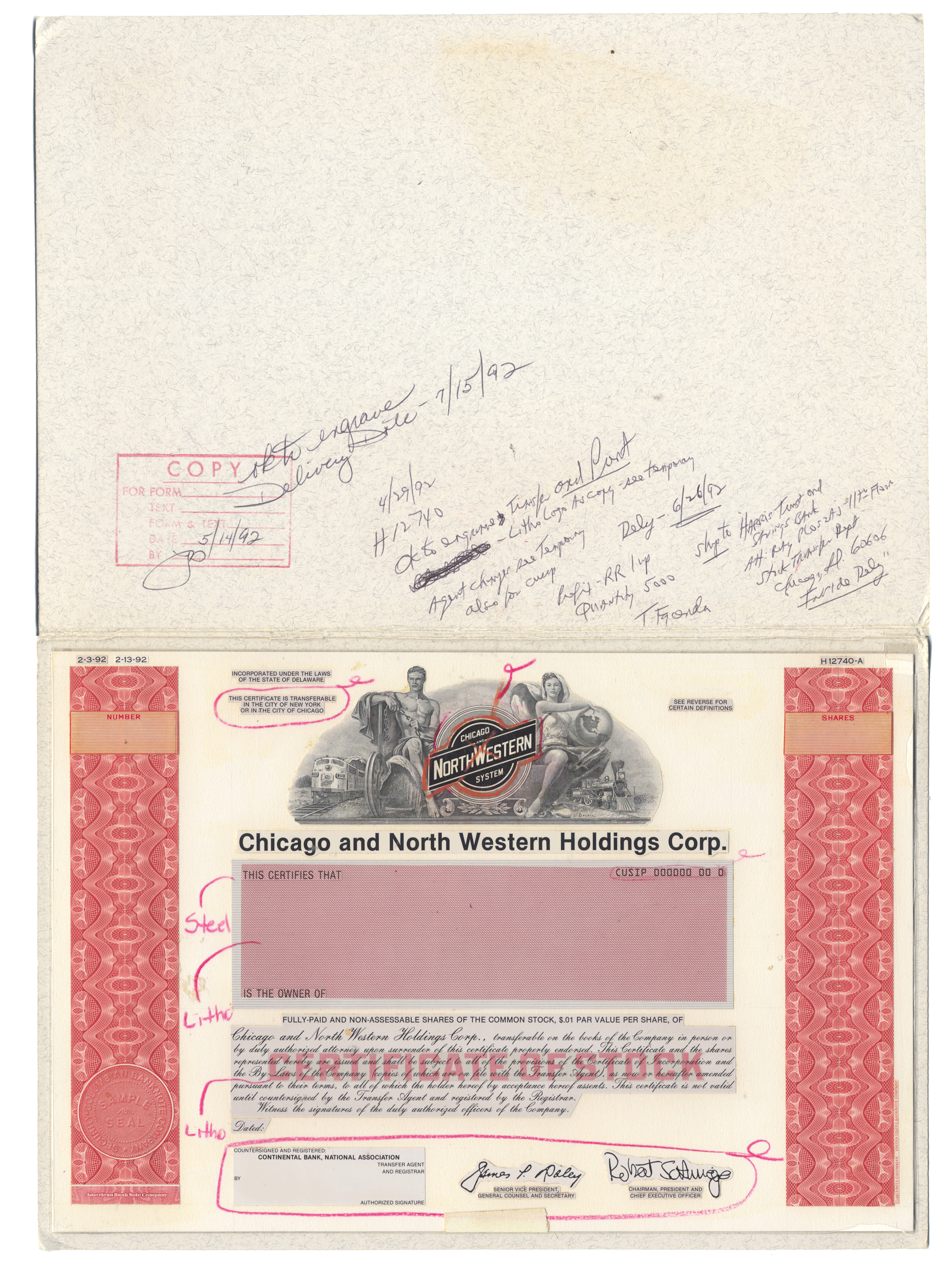

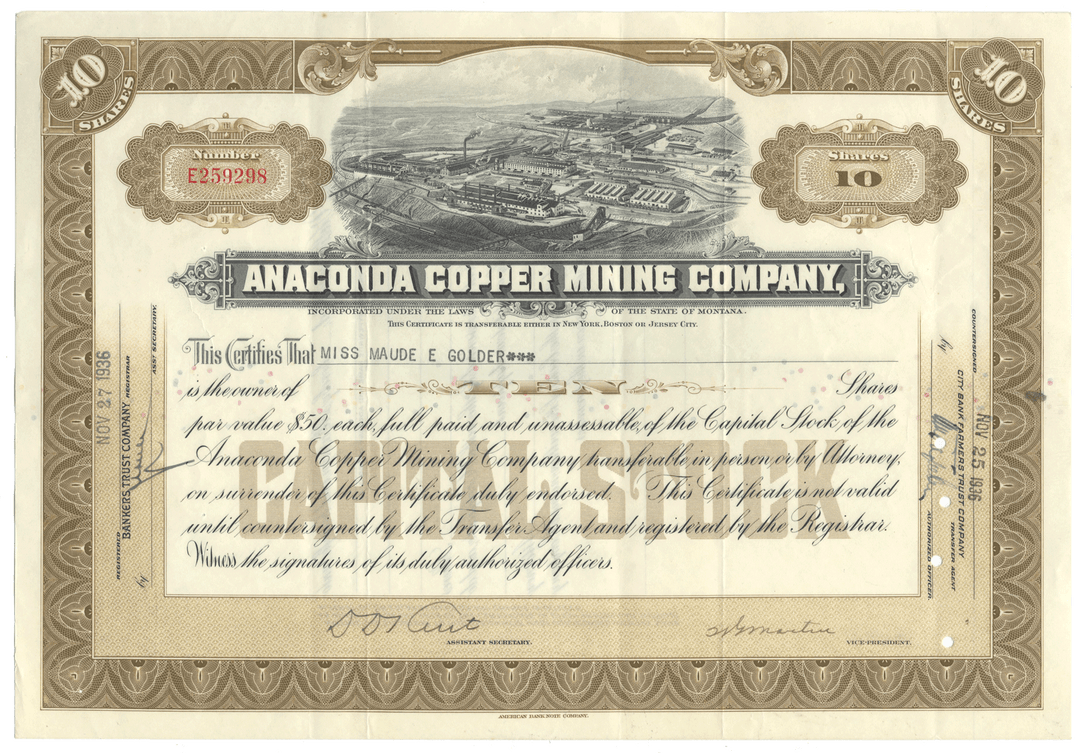

Anaconda Copper Mining Company

- Guaranteed authentic document

- Orders over $50 ship FREE to U. S. addresses

Product Details

Certificate Type

Capital Stock

Date Issued

November 25, 1936

Canceled

Yes

Printer

American Bank Note Company

Signatures

Machine printed

Approximate Size

12" (w) by 8" (h)

Additional Details

NA

Historical Context

The Anaconda Copper Mining Company was started in 1881 when Marcus Daly bought a small silver mine called Anaconda near Butte, Montana. At the time, Daly was working for the Walker Bros. (mining investors) of Salt Lake City, Utah as a mine manager and engineer of the Alice, a silver mine in Walkerville, a suburb of Butte. While working in the Alice, he noticed significant quantities of high grade copper ore. Daly obtained permission from the owner of the Anaconda and several other mines in the area, to inspect the workings. He was a geologist and knew the red mineral he was looking at. After Daly's employers refused to buy the Anaconda, Daly sold his interest in the Alice and bought it himself. Placer gold and silver lode mining had taken place at Butte, placer mining at Helena, Bannock and Virginia City, Montana territory. Daly asked George Hearst, San Francisco mining magnate, for additional support. Hearst agreed to buy one-fourth of the new company's stock without visiting the site. While mining the silver left in his mine, huge deposits of copper were soon developed and Daly became a copper magnate. When surrounding silver mines "played out" and closed, Daly quietly bought up the neighboring mines, forming a mining company. Daly built a smelter at Anaconda, Montana (a company town) and connected his smelter to Butte by a railway. Anaconda Company eventually owned all the mines on Butte Hill.

Butte, a small and poor town, became one of the most prosperous cities in the country, often called "the Richest Hill on Earth." From 1892 through 1903, the Anaconda mine was the largest copper-producing mine in the world. It produced more than $300 billion worth of metal in its lifetime.

In 1889 the Rothschilds tried to gain control of the world copper market. In 1892 the French Rothschilds began negotiations to buy the Anaconda mine. In mid-October 1895 the Rothschilds, French and British, bought one quarter of the stock in Anaconda for $7.5 million. By the late 1890s the Rothschilds probably had control over the sale of about forty percent of the world’s copper production.

The Rothschilds' role in Anaconda was brief. In 1899, Daly teamed up with two directors of Standard Oil to create the giant Amalgamated Copper Mining Company, one of the largest trusts of the early 20th century. The leading roles in the takeover were played by Henry Huttleston Rogers (John D. Rockefeller's friend and a key man in his Standard Oil businesses) and William Rockefeller (John's brother). They were aided by company promoter Thomas W. Lawson. Although Rogers and William Rockefeller were Standard Oil directors, the company of Standard Oil did not have a stake in this business, nor did its founder and head, John D. Rockefeller, who disliked such stock promotions.

By 1899 Amalgamated Copper acquired majority stock in the Anaconda Copper Company, and the Rothschilds appear to have had no further role in the company. By his death in 1900, Marcus Daly had just become president of the holding company valued at $75 million.

During the 1920s, metal prices went up and mining activity increased. Those were really the golden years for Anaconda. The company was managed by Ryan-Kelley team and was growing fast, expanding into the exploitation of new base metal resources: manganese, zinc and aluminum.

In 1922 the company acquired mining operations in Chile and Mexico.

The mining operation in Chile (Chuquicamata), was acquired from the Guggenheims in 1923. It cost Anaconda $77 million and was the largest copper mine in the world. It produced copper yielding two-thirds to three-fourths of the Anaconda Company's profits.

The same year ACM purchased American Brass Company, the nation's largest brass fabricator and a major consumer of copper and zinc. In 1926 Anaconda acquired the Giesche company, a large mining and industrial firm, operating in the Upper Silesia region of Poland. This nation had gained independence after World War I.

At that time Anaconda was the fourth-largest company in the world. These heady times, however, were short-lived.

In 1928 Ryan and Percy Rockefeller aggressively speculated on Anaconda shares, causing them to go up at first (at which point they sold) and then to go down (at which point they bought them back). Known today as a "pump and dump", at the time the actions were not illegal, and took place frequently. Under the pressure of a "joint account" set up by Ryan and Rockefeller of nearly a million and a half shares of Anaconda Copper Company, prices fluctuated from $40 in December 1928, to $128 in March 1929. Selling large volumes of shares rather quickly causes the bottom to fall out of the market, investors lose confidence and dump their shares, causing a domino effect.

Smaller investors were completely wiped out. The results are still considered one of the great fleecing's in Wall Street history. The United States Senate held hearings on the stock manipulations, concluding that those operations cost the public, at the very least, $150 million. A 1933 Senate banking committee called these operations the greatest frauds in American banking history, a leading cause of the 1929 stock market crash and 1930s depression.

In 1929, Anaconda Copper Mining Co. issued new stock and used some of the money to buy shares of speculative companies. When the market crashed on Oct. 29, 1929, Anaconda suffered serious financial setbacks. At the same time, copper prices started going down dramatically. During the winter of 1932–33, as the Depression expanded, copper prices dropped to 10.3 cents per pound, down from an average of 29.5 cents per pound only two years earlier.

The Great Depression took a toll in the mining industry; decline in demand led to the company making massive layoffs in both the United States and Chile (up to 66 percent unemployment rate in the Chilean mines). On March 26, 1931, Anaconda cut its dividend rate 40%. John D. Ryan died in 1933 and was buried in a copper coffin. His mighty Anaconda shares, once worth $175 each, had dropped to $4 at the bottom of the Great Depression. Cornelius Kelley became the Chairman in 1940.

The victory labor-management production committee of the Butte mines, September 1942. In the back row from left to right are: J.A. Livingston, Anaconda Copper Mining Company; E.I. Renouard, assistant general superintendent, ACM; H.J. Rahilly, assistant general superintendent, ACM; Charles Black, Butte miners' union; John Downs, boiler makers' union; W.J. McMahon, commissioner of labor of ACM; John F. Bird, electricians' union; J.P. Ryan, foreman of ACM; Ira Steck, superintendent, electrical department of ACM; James Cusick, machinists' union; John J. Mickelson, Butte miners' union; Eugene Hogan, superintendent ACM. In the front row reading from left to right are: E.S. McGlone, general superintendent, ACM; Bert Riley, Butte miners' union; Dennis McCarthy, Butte miners' union; A.C. Bigley, ACM; Carl Stenberg, painters' union; John Eathorne, foreman of ACM; John Gaffney, carpenters' union. Butte mining, like most U.S. industry, remained depressed until the dawn of World War II, when the demand for war materials greatly increased the need for copper, zinc, and manganese. Anaconda ranked 58th among United States corporations in the value of World War II-military production contracts. That relieved some of the economic tensions.

The end of World War II brought another depression in the copper industry because of a decline in demand after war production ended.

During the post-war years, demand and prices of copper dropped. At the same time mining costs had risen precipitously. As a result, copper production from Butte's underground vein mines dropped to only 45,000 mt annually. Anaconda tasked its engineers with devising new techniques to keep mining profitable. The answer was called the "Greater Butte Project" (GBP). The project would exploit lower-grade underground reserves by the block-caving method. Anaconda sank a new shaft, the Kelly, and the mine began producing in 1948. The new method was successful, although short-lived. They also began stripping ground for what was to become the Berkeley pit.

In 1956 Anaconda netted the largest annual income in its history: $111.5 million. After that year, ore grades continued their decline, mining costs were rising each year, and profits were diminishing. To survive, the company switched to open-pit mining, a very area-consuming method. The Berkeley Pit kept expanding and ate away at the older parts of Butte.

In 1971, Chile's newly elected Socialist president Salvador Allende confiscated the Chuquicamata mine from Anaconda--at one stroke, stripping Anaconda of two-thirds of its copper production. Allende was overthrown in 1973, and the successor government of Augusto Pinochet paid Anaconda compensation of $250 million.

Losses from the Chilean takeover, however, had seriously weakened the company's financial position. Later in 1971, Anaconda's Mexican copper mine Compañía Minera de Cananea, S.A. was nationalized by president Luis Echeverría Álvarez's government. An unwise investment in the unsuccessful Twin Buttes mine in southern Arizona further weakened the company. In 1977 Anaconda was sold to Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) for $700 million. However, the purchase turned out to be a regrettable decision for ARCO. Lack of experience with hard-rock mining, and a sudden drop in the price of copper to sixty-odd cents a pound, the lowest in years, caused ARCO to suspend all operations in Butte in 1980. ARCO shut off the deep pumps in 1982, and allowed the mines to fill with water.

Six years after ARCO acquired rights to the "Richest Hill on Earth", the Berkeley Pit was completely idle. ARCO founder, Robert Orville Anderson, stated "he hoped Anaconda's resources and expertise would help him launch a major shale-oil venture, but that the world oil glut and the declining price of petroleum made shale oil moot." At the time of the sale to ARCO, Anaconda had large working hard coal holdings in the Black Thunder mine at Thunder Basin, Wyoming. ARCO planned to diversify its energy business into coal. In June 1998, Arch Coal completed the acquisition of the coal assets of Atlantic Richfield.

Related Collections

Additional Information

Certificates carry no value on any of today's financial indexes and no transfer of ownership is implied. All items offered are collectible in nature only. So, you can frame them, but you can't cash them in!

All of our pieces are original - we do not sell reproductions. If you ever find out that one of our pieces is not authentic, you may return it for a full refund of the purchase price and any associated shipping charges.