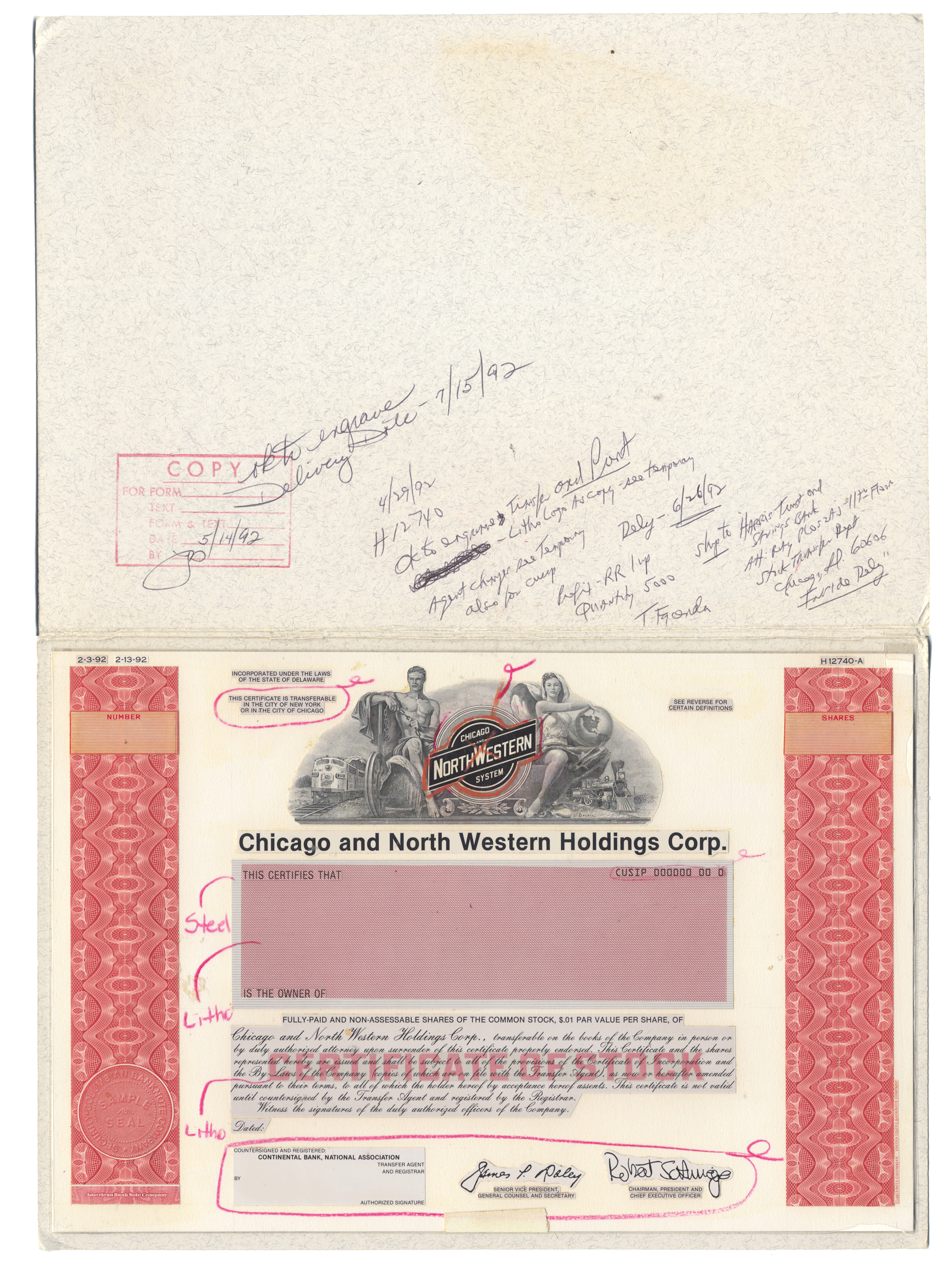

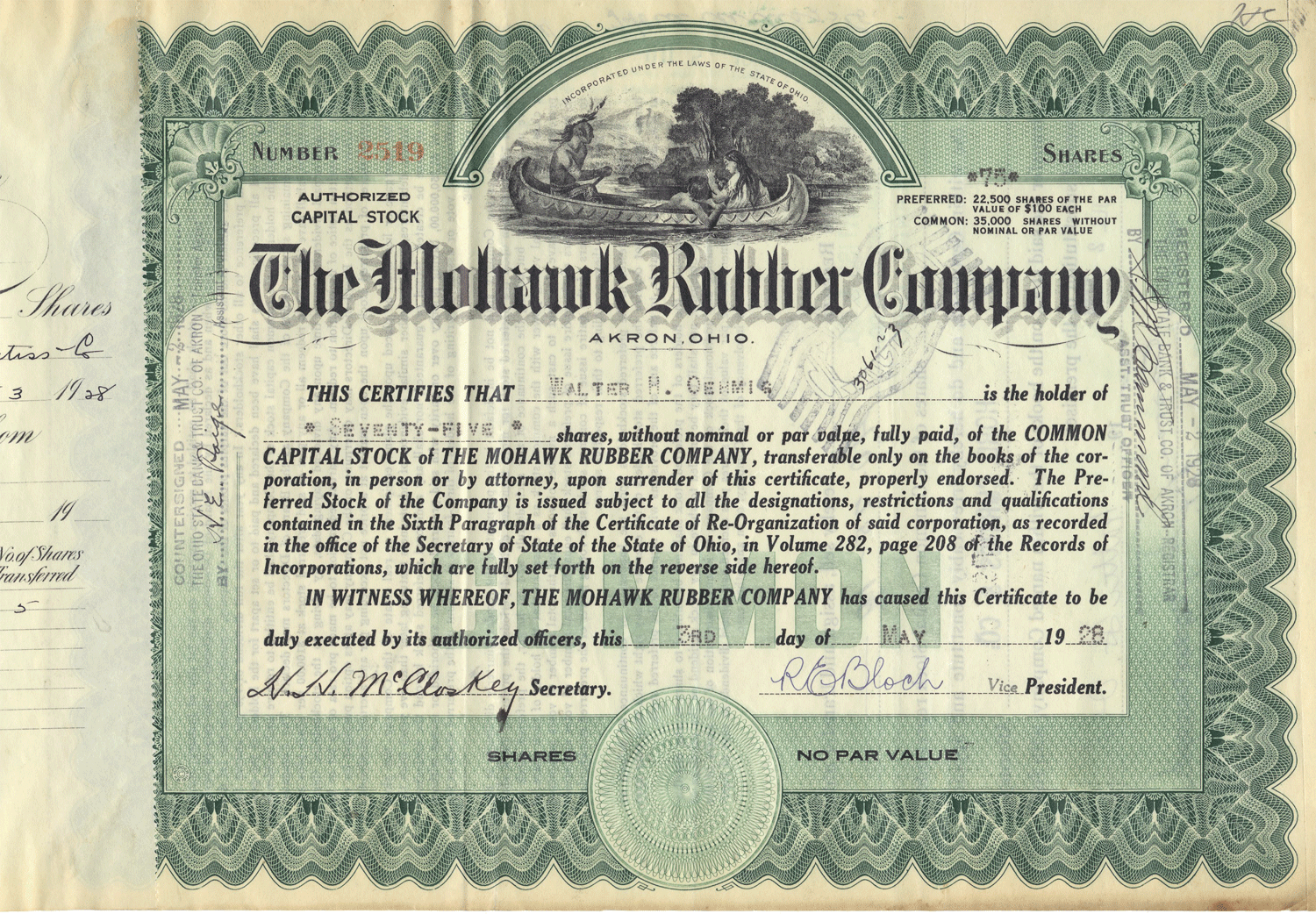

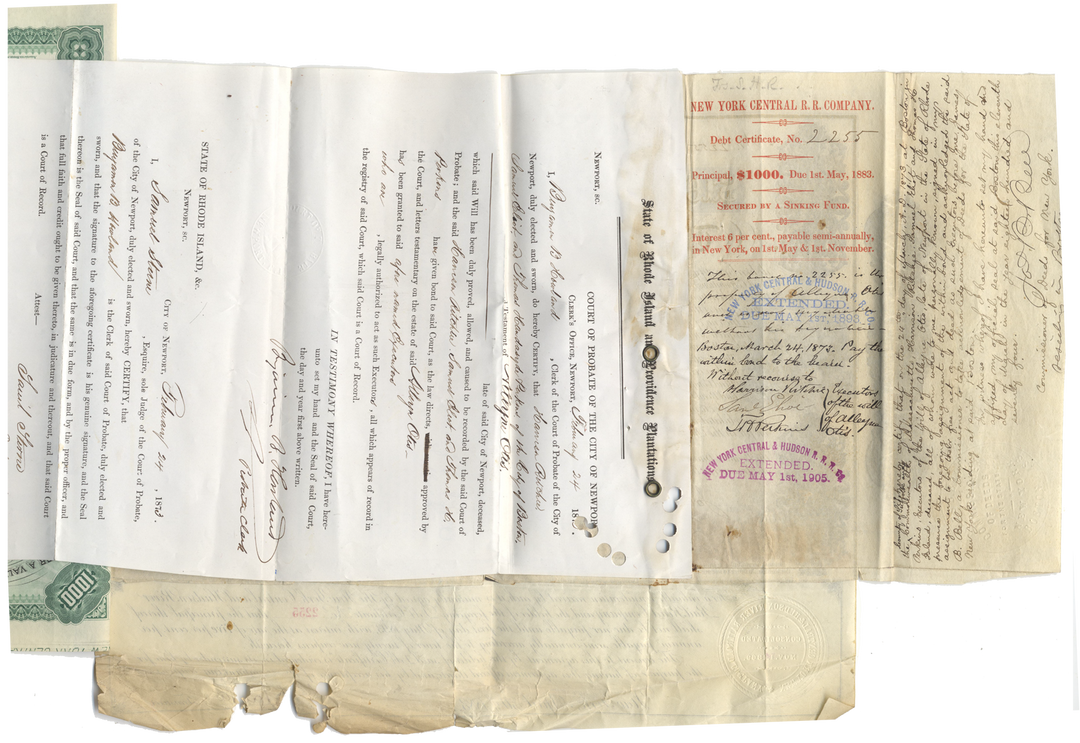

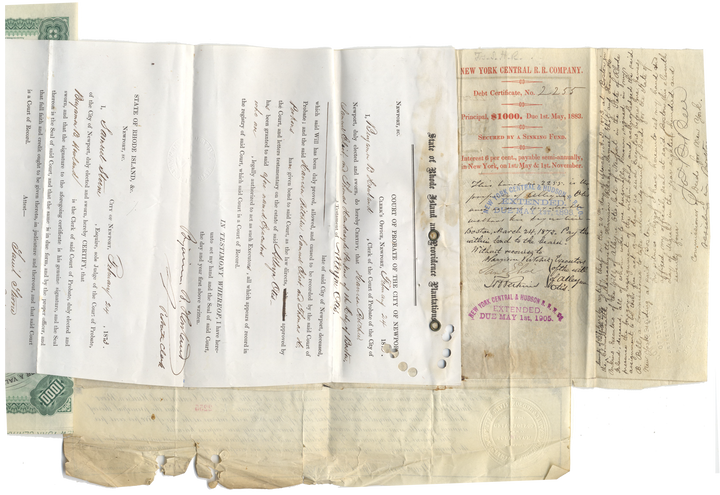

New York Central Rail Road Company (Signed by Erastus Corning)

- Guaranteed authentic document

- Orders over $50 ship FREE to U. S. addresses

You will receive the exact certificate pictured

Guaranteed authentic

Over 150 years old

Gold bond

August 1, 1853

Issued, canceled

Not indicated

Hand signed

12 1/2" (w) by 10" (h)

Signed by Erastus Corning

Erastus Corning

Erastus Corning, businessman and politician, was born in Norwich, Connecticut. Corning moved to Troy, New York at the age of 13 to clerk in the hardware store of an uncle; six years later he moved to Albany, New York, where he joined the mercantile business under James Spencer. After some time at Spencer's firm, Corning became a partner, and eventually the senior partner upon Spencer's death in 1824. Corning combined the Spencer firm with holdings he inherited from his uncle to form Erastus Corning & Company.

Erastus Corning & Company

Erastus Corning & Co. was much more than what modern readers think of as a hardware store. Corning bought and sold all manner of iron products, not merely tools and nails as one would expect but also stoves, farming equipment, and, eventually, rails and railroad iron parts and products. The company had a wharf and warehouse on the Hudson River in Albany, and the store itself served not only Albany and the surrounding towns, but hundreds of large customers from the west who visited Albany only two or three times a year to buy and sell products, restock their own supplies, and see what new was for sale. Corning's hardware store soon became one of the most significant businesses in Albany.

Corning was not content to run a hardware store, however, no matter how big the store might be. About the time he was consolidating his holdings into Erastus Corning & Co., he was also investing in banks and insurance companies. He purchased the Albany Rolling and Slitting Mill, renamed it the Albany Nail Factory, and used it to corner the market on numerous of the iron products he sold at his store. The Albany Nail Factory eventually became the Rensselaer Iron Works, which, under Corning's guidance, installed the first Bessemer converter in the United States.

By the time he was 40, Corning had helped found the Albany State Bank (he would serve as president until his death), been named to the board of the University of the State of New York, begun speculating on land in western New York (including the townsite that bears his name), and had gotten himself elected mayor of Albany. Corning served a single term as mayor, from 1834 until 1837, having been elected as a Democrat.

Railroads

Erastus Corning's most lasting contribution to history may have been his dealings with railroads. As an iron dealer, he very quickly saw the potential that railroads had as an economic engine as both a consumer and distributor of his products, and took an interest from the very start. When the Utica & Schenectady Railroad was chartered in 1833, Corning got himself a seat on the board and became a major investor, and was soon president of the road. Corning ran the Utica & Schenectady for twenty years. The railroad eventually boasted 78 miles of track, from Schenectady in the east (where the road interchanged with the smaller Mohawk & Hudson Railroad of which Corning was also a shareholder) to Utica in the west. In 1851, the road's name was changed to the Mohawk Valley Railroad.

Corning was not satisfied with just his railroad, banking, insurance, land speculation, and iron works interests, however. He continued to dabble in politics, being elected in 1842 to the New York state senate for a single term. His foray into state politics convinced him that the current system of railroads stretching across upstate New York was inefficient and could be made far more profitable by combining them. He began planning what would eventually become the largest corporation in America at the time, the New York Central.

As president of the Utica & Schenectady, Corning organized in 1851 a convention of the owners and presidents of the other eight operating railroads, which combined roughly connected the cities of Albany and Buffalo, New York. The convention agreed on a framework for consolidation of the eight roads (as well as two paper roads, which had not yet been built but were planned), and Corning took the convention's application to the state Legislature. Corning became the main lobbyist for the proposal in the legislature, and despite being a Democrat made a personal appeal to Thurlow Weed, leader of the Whigs, who controlled state government at the time.

Corning had a lot riding on the legislature's decision. He had organized the convention and largely dictated the terms of the merger to the other companies. Once the legislature passed the Consolidation Act on April 2, 1853, Corning found himself in possession of the majority of shares in the new company, and so at the first meeting of the New York Central's shareholders in 1853, Corning got himself elected president of the company. He remained in that role for twelve years, during which time the New York Central made connections and struck deals that gave the road access to Cleveland, Boston, New York City, and Chicago, and made it one of the country's most important railroads.

Corning amassed a significant fortune, and used it to invest in land schemes as far west as Wisconsin and Iowa. He bought large shares in the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad and the Michigan Central Railroad, and was the largest shareholder in and president of the St. Mary's Falls Ship Canal Company, which constructed the canal and locks on the St. Mary's River at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, connecting Lake Superior with Lake Huron. For this the company received 750,000 acres of land in the west; Corning himself took 100,000 acres of this.

Civil War Politics

In 1856, shortly after finishing the St. Mary's River project, Corning was nominated for and won a seat in the United States Congress from New York. He did not stand for re-election in 1858, but was elected to a second term in 1860; he also served as a New York delegate to the Democratic National Convention that year. In 1861, before taking office in Congress, he was a delegate to the Peace Congress in Washington, D.C., but once the Civil War began he took his seat in Congress and, at least initially, supported the Lincoln Administration. He served out this term, and was elected again in 1862, but resigned his post because of failing health and disagreements with the Lincoln Administration over prosecution of the Civil War.

Back home in Albany, Corning organized a public meeting on the war, which resulted in a formal letter sent to Abraham Lincoln under Corning's hand offering support for maintaining the integrity of the Union, but censuring the administration for certain tactics it was employing in the war, most notably the making of military arrests of civilians in New York accused of avoiding service. This incident is notable for the response it generated from President Lincoln, a lengthy letter wherein the president sets out his views on what the Constitution allowed him to do in wartime.

Despite his disagreements with Lincoln's handling of the war, Corning fully supported the effort to maintain the Union. The United States Navy contracted with Corning's iron works to manufacture parts and materials for the USS Monitor, the Navy's first ironclad warship.

Corning’s Later Years

Corning's personal papers make little reference to the nature of his ill health, but from his retirement on, Corning slowly began reducing his commitments and public activities. Through the 1860's he began to focus more on land speculation and less on his business holdings. He resigned from the New York Central in 1865, two years before the railroad was bought out by Cornelius Vanderbilt. In 1867, Corning was a delegate to the New York State Constitutional Convention. It was his last public office.

By 1871, Corning had passed control of his business interests on to his sons and close associates, and at one point passed up the opportunity to buy a share in a new land deal in Nebraska, saying that "I find that my health is such that it will not do for me to take hold of any new undertaking." He remained on the board of the Albany State Bank, and also continued as vice chancellor of the board of regents of the University of the State of New York, positions he had held by that time for over 30 years. He died at home in Albany in April, 1872.

Corning's grandsons Edwin and Parker Corning both held various political positions in the state of New York in the early 1900s. His great-grandson, Erastus Corning II, was mayor of Albany for over 40 years, from 1941 to 1983. The Rensselaer Iron Works eventually became part of the larger Troy Iron & Steel Company, in its time the largest iron and steel manufacturer in the United States, but the company eventually went out of business. The New York Central remained one of the most significant American railroads through the end of the 19th Century; it was eventually merged with its arch-rival the Pennsy (Pennsylvania Railroad) and ultimately became a part of Conrail in the 1970s. Parts of the New York Central, including parts of the original Utica & Schenectady, are still in use today by CSX. The locks on the St. Mary's River remain the busiest locks in the world. Erastus Corning's personal papers, almost 50,000 pages worth, are held by the libraries of Cornell University.

Additional Information

Certificates carry no value on any of today's financial indexes and no transfer of ownership is implied. All items offered are collectible in nature only. So, you can frame them, but you can't cash them in!

All of our pieces are original - we do not sell reproductions. If you ever find out that one of our pieces is not authentic, you may return it for a full refund of the purchase price and any associated shipping charges.