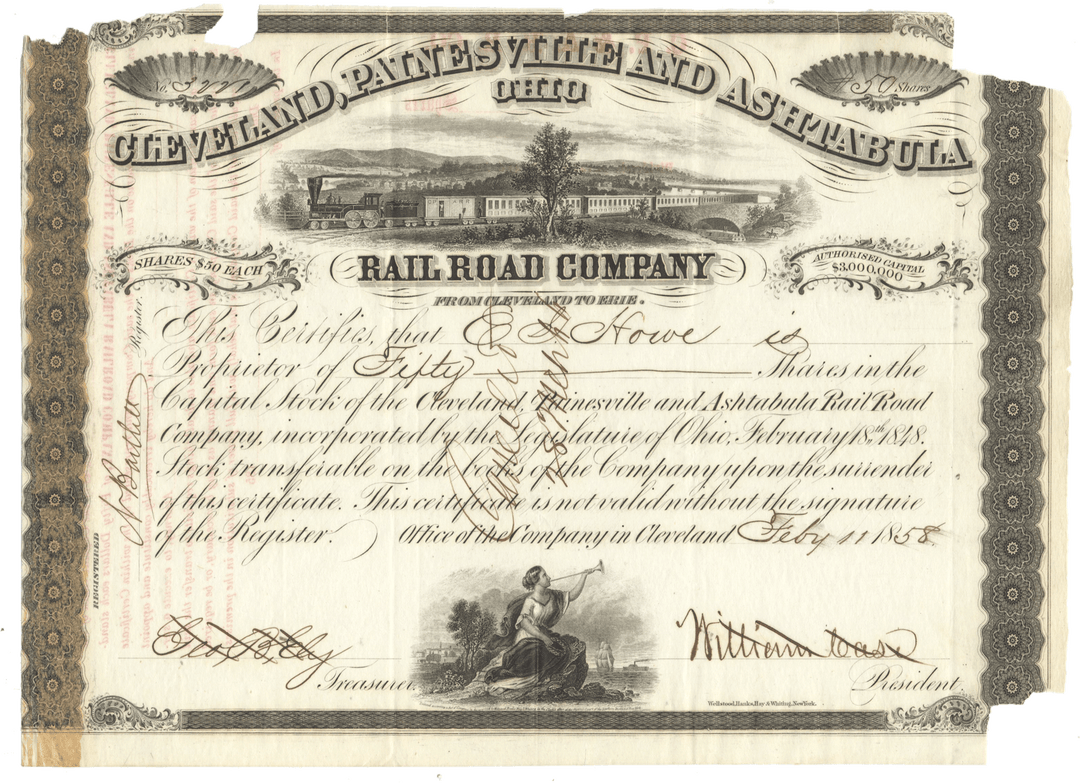

Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Rail Road Company

- In stock

- Backordered, shipping soon

- Guaranteed authentic document

- Orders over $35 ship FREE to U. S. addresses

Product Details

Company

Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Rail Road Company

Certificate Type

Capital Stock

Date Issued

February11, 1858

Canceled

Yes

Printer

Wellstood, Hanks, Hay & Whiting of New York

Signatures

Hand signed

Approximate Size

10" (w) by 7 1/2" (h)

Images

Show the exact certificate you will receive

Guaranteed Authentic

Yes

Additional Details

Please review condition carefully

Reference

Historical Context

Cleveland had emerged as one of the largest and fastest-growing cities in Ohio due to its transportation links (the Ohio and Erie Canal and its Lake Erie steamship port). Railroads were seen by Cleveland business and civic leaders as critical to the city's future. They could reach deep into agricultural and mining country far more easily than canals, and move much greater quantities of goods than wagons. Railroads would not only allow these goods to reach Erie and Buffalo (the traditional transshipment ports for Ohio products) faster and more easily, but also give Ohio producers direct access to large, rich seaboard cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. With Ohio underdeveloped and starved for capital, Clevelanders and other Ohioans saw railroads as the means to opening new markets and bringing capital into the state.

Alfred Kelley, a Cleveland lawyer, had been elected the first mayor of the newly-incorporated Village of Cleveland in 1815. As a member of the Ohio General Assembly, he championed the construction of canals, and as the first Canal Commissioner oversaw the construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal. Known as the "father of the Ohio and Erie Canal", Kelley was one of the most dominant commercial, financial, and political people in the state of Ohio in the first half of the 1800s. In August 1847, the officers of the nascent Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad (CCC) asked Kelley to oversee construction of their new road. Kelley said yes, and the line from Cleveland to Columbus and Cincinnati was completed in February 1851.

With completion of the CCC, rail lines extended west and south of Cleveland—but not east to the all-important seaboard markets. Since 1831, different coalitions of Cleveland businessmen had tried to organize a railroad to connect Cleveland with points east, but none of these efforts got off the ground. In 1847, a group of businessmen from Ashtabula, Cuyahoga, and Lake counties undertook a successful effort to build Cleveland's railroad link to the east. The group included John W. Allen, Sergeant Currier, Charles Hickox, and John B. Waring of Cuyahoga County; William W. Branch, O.A. Crary, David R. Paige, Peleg Phelps Sanford, Lord Sterling, Aaron Wilcox, and Eli T. Wilder of Lake County; and Frederick Carlisle, George G. Gillett, Edwin Harmon, Zaphna Lake, Robert Lyon, and Asaph Turner of Ashtabula County. The Cuyahoga County representatives took the lead, and on February 18, 1848, they received a state charter for the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad (CP&A) to build a rail line from Cleveland to some point on the Ohio-Pennsylvania border.

The CP&A had a number of nicknames, and was also known informally as the "Cleveland and Erie Railroad", the "Cleveland and Buffalo Railroad", and the "Lake Shore Railroad".

Frederick Harbach, a surveyor and engineer for several Ohio railroads, surveyed the route for the CP&A in late 1849 and early 1850. In his report, issued at end of March 1850, Harbach proposed two routes. The "South Route" began at the City Station of the CCC on Station Street (an area south of what is now the intersection of Superior Avenue and W. 9th Street). It followed the towpath of the Ohio & Erie Canal south to Kingsbury Run, the moved inland along the stream, following it northeast and east to Euclid Creek. The route then turned north-northeast to Willoughby, where it crossed the Chagrin River. Past the river, the proposed route followed a fairly straight line along the lakeshore to the Ohio-Pennsylvania state border. The "North Route" began at the "Outer Station" of the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad (on E. 33rd Street between Lakeside and Hamilton Avenues) and followed a relatively straight route along the lake to Euclid Creek and Willoughby. Staying close to the shoreline, it passed 0.66 miles north of Painesville. The proposed route ran parallel to and north of the South Route at a distance of about 1.5 miles until reaching the Ohio-Pennsylvania state border.

Alfred Kelley reviewed both proposed routes, and chose the North Route. In part, this route was chosen because, east of Cleveland, it ran atop an ancient beach ridge (formed when Lake Erie was much larger) that required little ballasting, was naturally well-drained, and required almost no blasting or earth moving. It was also essentially a level grade for almost its entire length, with a ruling gradient of just 0.3 percent.

Construction on the CP&A began in January 1851. Due to the almost flat and obstacle-free route, grading proceeded very swiftly. By the end of the month, grading had reached Willoughby and a construction team was already at work in Painesville building a bridge over the Grand River. The bridge at Willoughby was completed in August, piers for the bridge in Ashtabula were under construction, and grading had proceeded past that city. The bridge at Painesville, begun May 26, was completed on October 6.

Ten months after construction began, the entire right of way to the Ohio-Pennsylvania border had been purchased, two-thirds (60 miles) of the road had been graded (to Ashtabula and slightly beyond), and all bridges completed except for the bridge over Conneaut Creek. For the track, the company purchased 65-pound T rails manufactured in the United Kingdom. Each rail was 12 to 18 feet in length, and joined by a cast iron chair joint. Ballast was not initially laid, although the unstable nature of the clay beneath the track bed later required it. White oak ties were used to anchor the track.

The track to Conneaut was completed on November 15, and a wooden Howe truss bridge built over Conneaut Creek to give access to the state border. Regular trains began running on the 71-mile line on November 20, 1851.

The CP&A did not have the legal authority to build a railroad in Pennsylvania. Until the late 1800s, states strictly controlled railroad development by requiring the issuance of charters by their legislatures, and they generally refused to give "foreign" (out-of-state) railroads permission to own or construct railroads within their borders. Moreover, the Pennsylvania state legislature prohibited the construction of railroads across the Erie Triangle, effectively blocking both New York and Ohio railroads from crossing the state there.

The CP&A soon discovered a way around this legal obstacle. In April 1844, the Pennsylvania General Assembly had enacted legislation incorporating the Franklin Canal Company (FCC) and permitted the company to take ownership of the Franklin Division of the Pennsylvania Canal between the French Creek feeder aqueduct at Meadville and the mouth of French Creek at Franklin. The company discovered that the canal would never become profitable, and petitioned the state to expand its charter. The state legislature did so in April 1849, permitting the FCC to build a railroad along the Franklin Division canal towpath and to extend this railroad line north to Lake Erie and south to Pittsburgh (where it could connect with other railroads). Two months later, the FCC concluded that the connection clause in its charter permitted it to expand westward as well. The company established a subsidiary (the "Erie and Cleveland Railroad") to build and operate this 25.5 miles line.

The line eventually became part of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern.

Related Collections

Additional Information

Certificates carry no value on any of today's financial indexes and no transfer of ownership is implied. All items offered are collectible in nature only. So, you can frame them, but you can't cash them in!

All of our pieces are original - we do not sell reproductions. If you ever find out that one of our pieces is not authentic, you may return it for a full refund of the purchase price and any associated shipping charges.