STORE CLOSING!

Everything is 60% off. Prices as marked. Orders placed after January 22nd, will ship on February 6th.

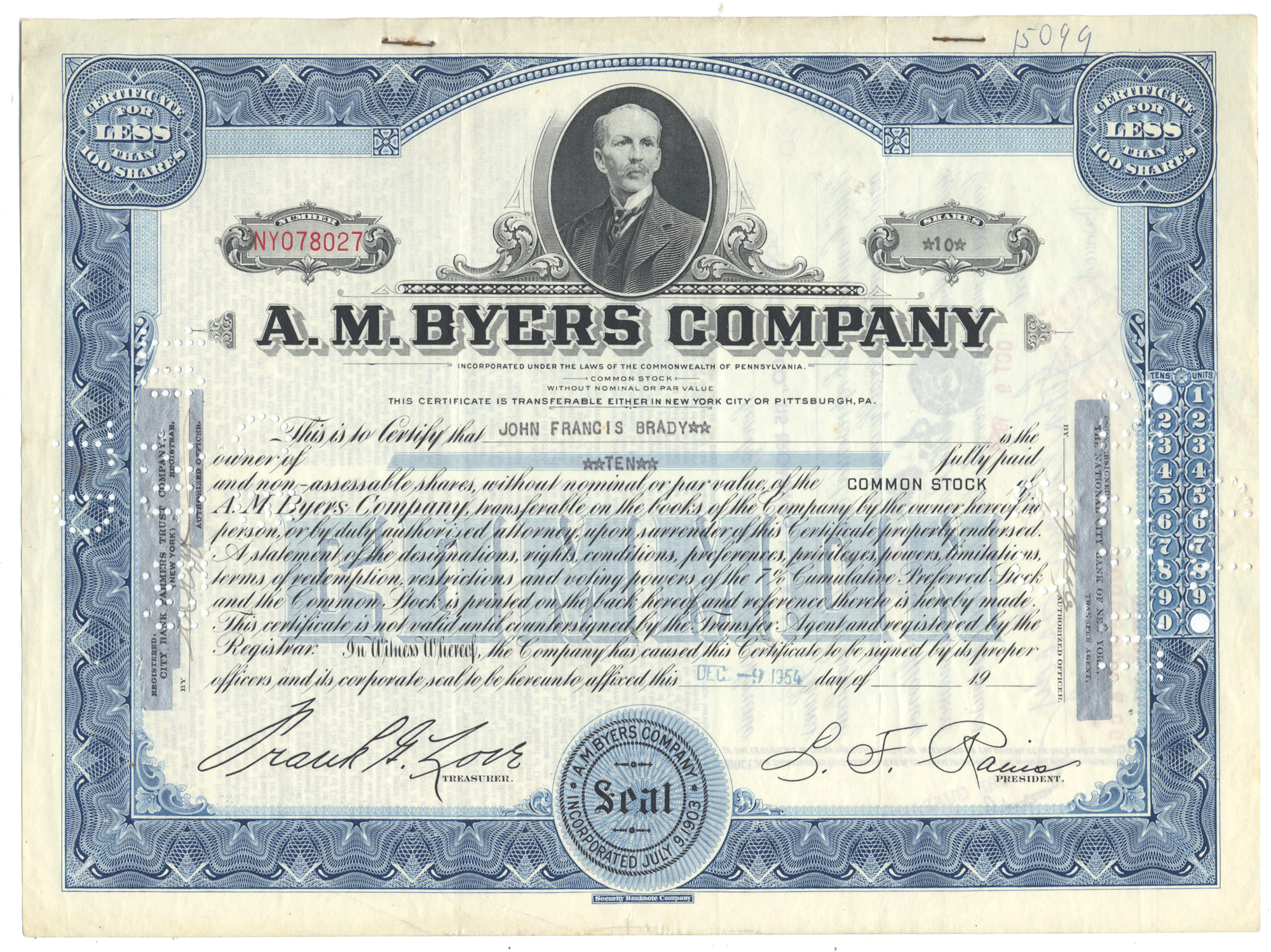

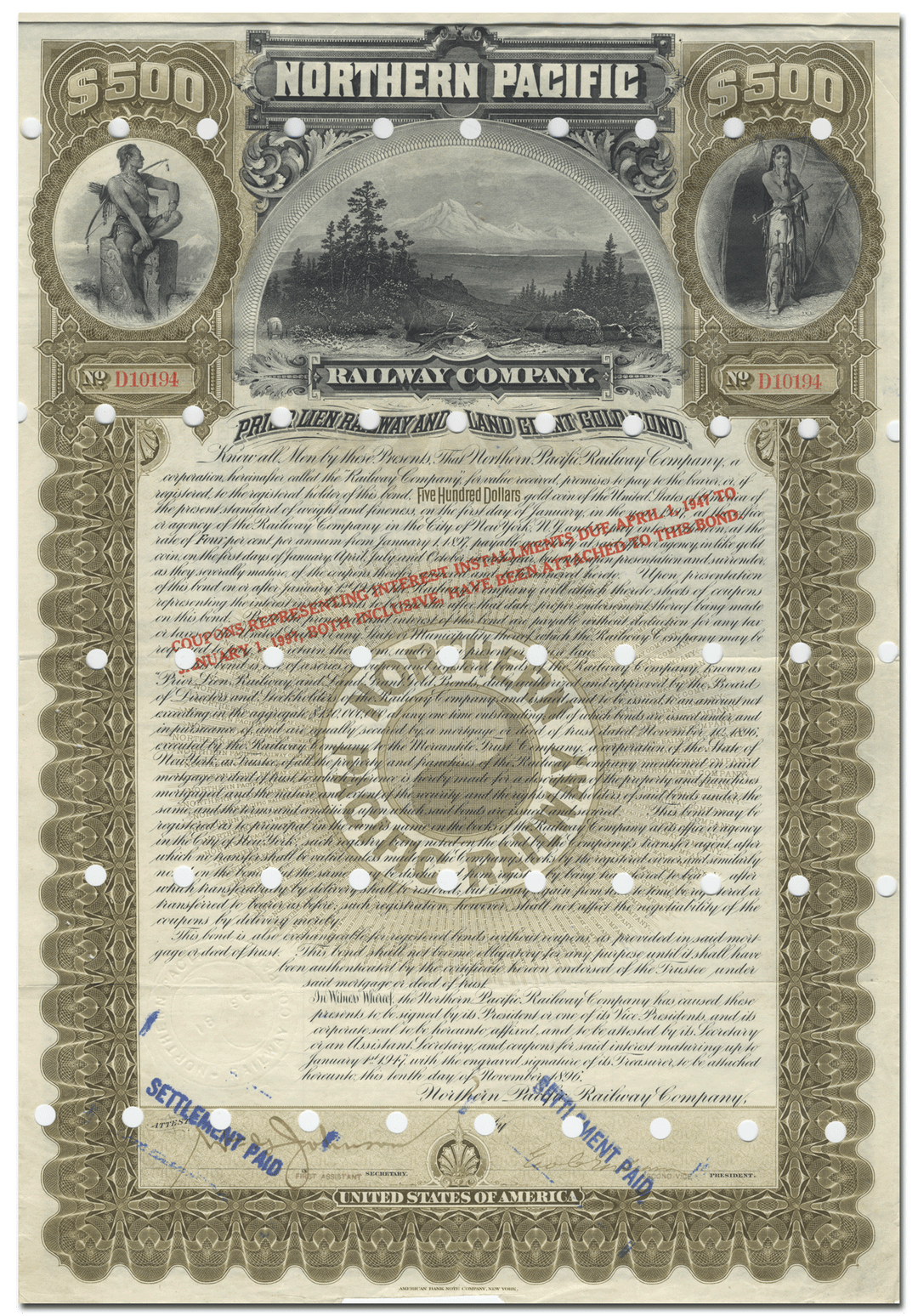

All of our pieces are genuine - we do not sell reproductions. If you ever find out that one of our pieces is not authentic, you may return it for a full refund of the purchase price and any associated shipping charges.

Certificates carry no value on any of today's financial indexes and no transfer of ownership is implied. All items offered are collectible in nature only. So, you can frame them, but you can't cash them in!

It depends. We try to present images of the exact piece you will receive whenever possible. However, when we are offering quantities of a piece, this is impossible. Within every product page we detail whether or not you will be receiving the exact certificate listed, or if the image is a representative example of the one you will receive.

We ship all orders via the United States Postal Service. Most domestic orders are shipped via Ground Advantage. USPS International, Priority and Express Mail, UPS and DHL services are also available, and costs are calculated during checkout. Current charges may be reviewed here.

Absolutely. You may return any merchandise, for any reason, within 30 days of the purchase date for a full refund of the purchase price.

We guarantee all of our pieces to be authentic. If you ever determine that a piece is not authentic, it may be returned for a full refund of the purchase price as well as any associated shipping charges.

Yes. We purchase old stocks and bonds as collectible pieces. Feel free to contact us or use our chat system to let us know what you have. We will get back to you as soon as we can!

No we do not. You would need to have a firm that specializes in such a search to determine if your stock or bond remains negotiable. We buy and sell stocks and bonds as collectible pieces only.