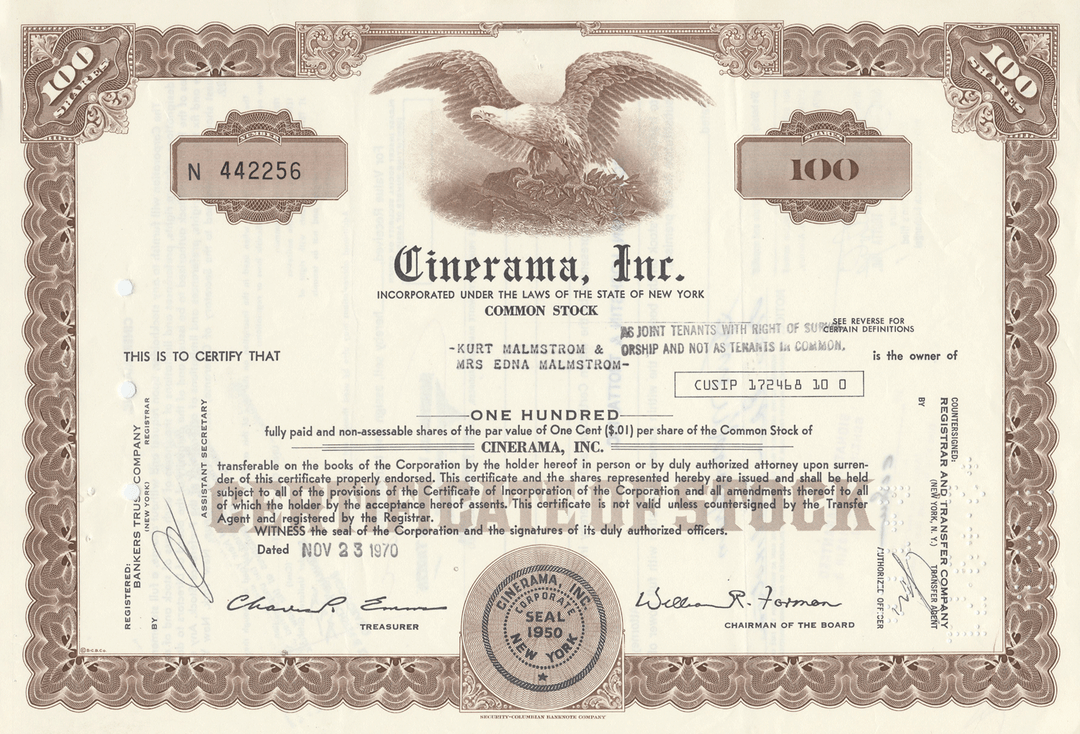

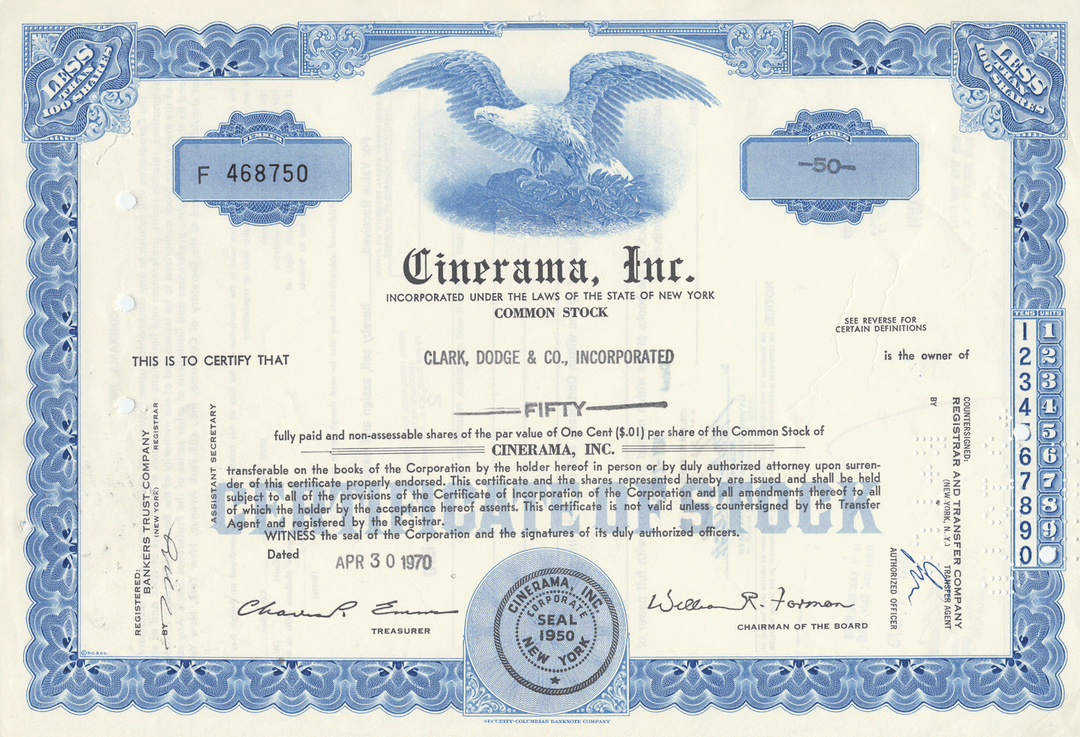

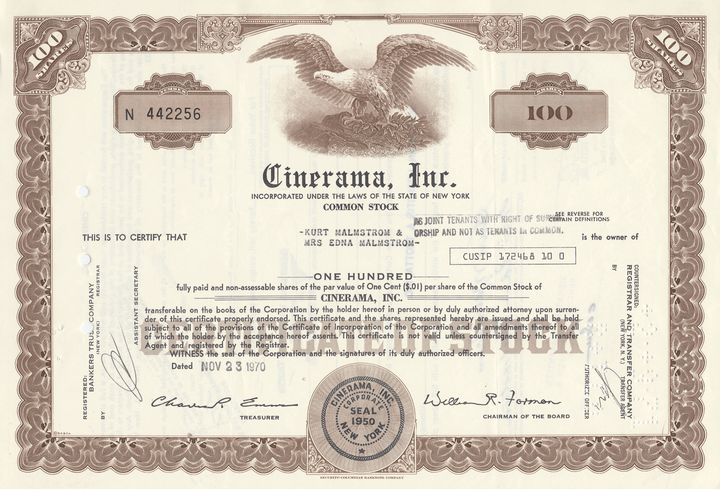

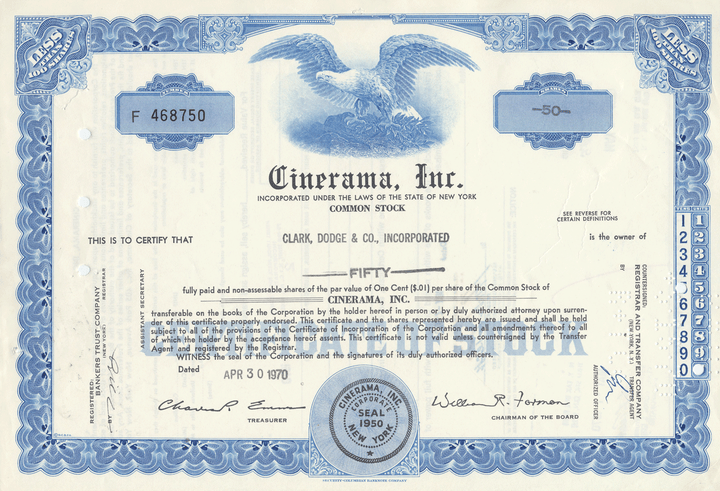

Cinerama, Inc.

- Guaranteed authentic document

- Orders over $100 ship FREE to U. S. addresses

Product Details

Cinerama, Inc.

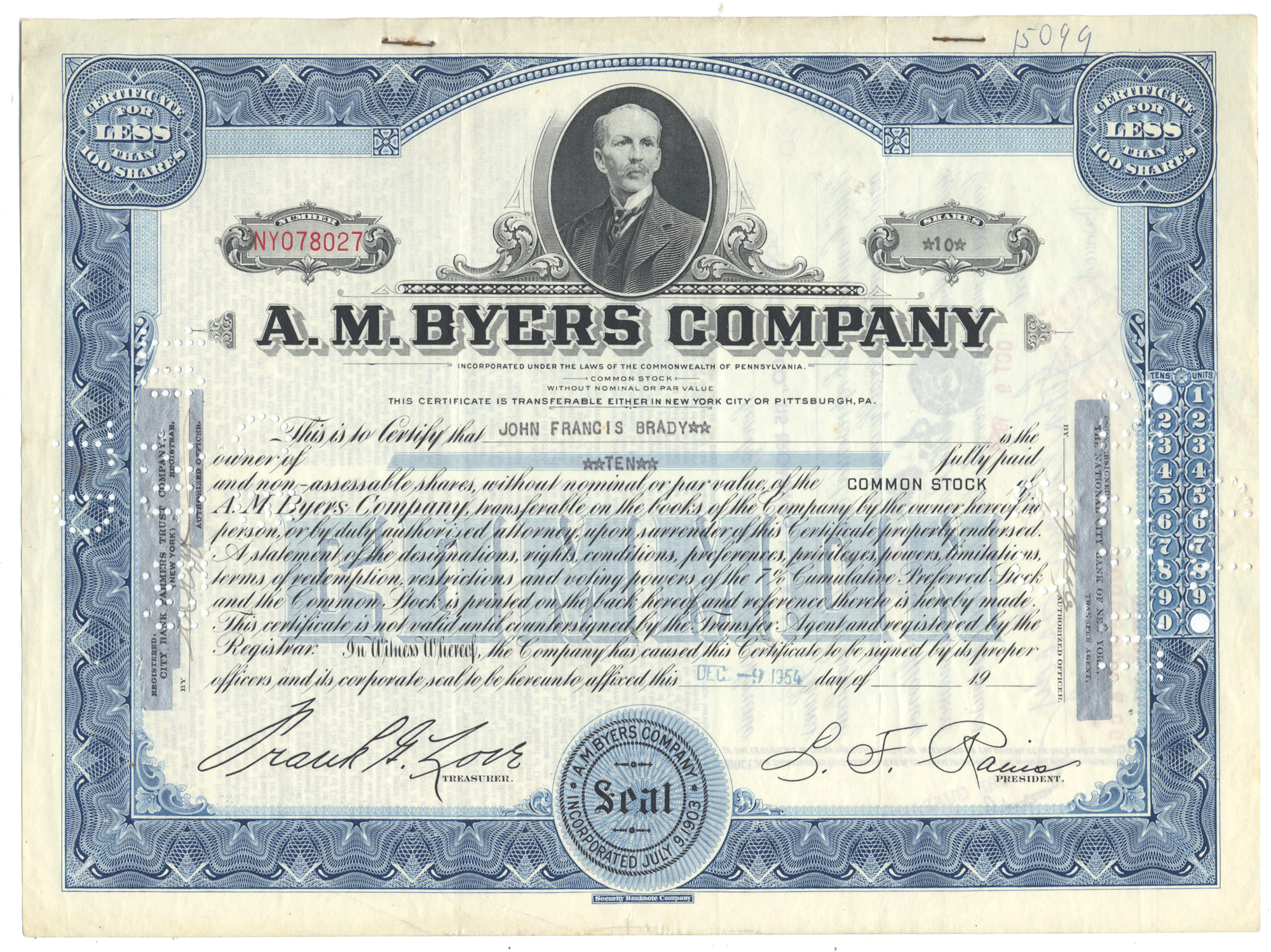

Certificate Type

Common Stock

Date Issued

1970's

Canceled

Yes

Printer

Security-Columbian Bank Note Company

Signatures

Machine printed

Approximate Size

12" (w) by 8" (h)

Additional Details

NA

Historical Context

Cinerama was invented by Fred Waller (1886–1954) and languished in the laboratory for several years before Waller, joined by Hazard "Buzz" Reeves, brought it to the attention of Lowell Thomas who, first with Mike Todd and later with Merian C. Cooper, produced a commercially viable demonstration of Cinerama that opened on Broadway on September 30, 1952. The film, titled This is Cinerama, was received with enthusiasm. It was the outgrowth of many years of development. A forerunner was the triple-screen final sequence in the silent Napoléon (1927) directed by Abel Gance; Gance's classic was considered lost in the 1950s, however, known of only by hearsay, and Waller could not have actually viewed it. Waller had earlier developed an 11-projector system called "Vitarama" at the Petroleum Industry exhibit in the 1939 New York World's Fair. A five-camera version, the Waller Gunnery Trainer, was used during the Second World War.

The word "Cinerama" combines cinema with panorama, the origin of all the "-orama" neologisms (the word "panorama" comes from the Greek words "pan", meaning all, and "orama", which translates into that which is seen, a sight, or a spectacle). It has been suggested that Cinerama could have been an intentional anagram of the word American; but an online posting by Dick Babish, describing the meeting at which it was named, says that this is "purely accidental, however delightful."

The photographic system used three interlocked 35 mm cameras equipped with 27 mm lenses, approximately the focal length of the human eye. Each camera photographed one third of the picture shooting in a crisscross pattern, the right camera shooting the left part of the image, the left camera shooting the right part of the image and the center camera shooting straight ahead. The three cameras were mounted as one unit, set at 48 degrees to each other. A single rotating shutter in front of the three lenses assured simultaneous exposure on each of the films. The three angled cameras photographed an image that was not only three times as wide as a standard film but covered 146 degrees of arc, close to the human field of vision, including peripheral vision. The image was photographed six sprocket holes high, rather than the usual four used in conventional 35 mm processes. The picture was photographed and projected at 26 frames per second rather than the usual 24.

According to film historian Martin Hart, in the original Cinerama system "the camera aspect ratio [was] 2.59:1" with an "optimum screen image, with no architectural constraints, [of] about 2.65:1, with the extreme top and bottom cropped slightly to hide anomalies". He further comments on the unreliability of "numerous websites and other resources that will tell you that Cinerama had an aspect ratio of up to 3:1."

In theaters, Cinerama film was projected from three projection booths arranged in the same crisscross pattern as the cameras. They projected onto a deeply curved screen, the outer thirds of which were made of over 1100 strips of material mounted on "louvers" like a vertical venetian blind, to prevent light projected to each end of the screen from reflecting to the opposite end and washing out the image. This was a big-ticket, reserved-seats spectacle, and the Cinerama projectors were adjusted carefully and operated skillfully. To prevent adjacent images from creating an overilluminated vertical band where they overlapped on the screen, vibrating combs in the projectors, called "jiggolos," alternately blocked the image from one projector and then the other; the overlapping area thus received no more total illumination than the rest of the screen, and the rapidly alternating images within the overlap smoothed out the visual transition between adjacent image "panels." Great care was taken to match color and brightness when producing the prints. Nevertheless, the seams between panels were usually noticeable. Optical limitations with the design of the camera itself meant that if distant scenes joined perfectly, closer objects did not (parallax error). A nearby object might split into two as it crossed the seams. To avoid calling attention to the seams, scenes were often composed with unimportant objects such as trees or posts at the seams, and action was blocked so as to center actors within panels. This gave a distinctly "triptych-like" appearance to the composition even when the seams themselves were not obvious. It was often necessary to have actors in different sections "cheat" where they looked in order to appear to be looking at each other in the final projected picture. Enthusiasts say the seams were not obtrusive; detractors disagree. Lowell Thomas, an investor in the company with Mike Todd, was still raving about the process in his memoirs thirty years later.

In addition to the visual impact of the image, Cinerama was one of the first processes to use multitrack magnetic sound. The system, developed by Hazard E. Reeves, one of the Cinerama investors, played back from a full coated 35 mm magnetic film with seven tracks of sound targeting a speaker layout similar to the more modern SDDS. There were five speakers behind the screen, two on the side and back of the auditorium with a sound engineer directing the sound between the surround speakers according to a script. The projectors and sound system were synchronized by a system using selsyn motors.

The Cinerama system had some obvious drawbacks. If one of the films should break, it had to be repaired with a black slug exactly equal to the missing footage. Otherwise, the corresponding frames would have had to be cut from the other three films (the other two picture films plus the soundtrack film) in order to preserve synchronization. The use of zoom lenses was impossible since the three images would no longer match. Perhaps the greatest limitation of the process is that the picture looks natural only from within a rather limited "sweet spot." Viewed from outside the sweet spot, the picture can look distorted.

The system also required a bit of improvisation on the part of the film producers. It was not possible to film any scene where any part of the scene was close to the camera, as the fields of view no longer met exactly. Further, any close-up material had a noticeable bend in it at the joins. It was also difficult to film actors talking to each other where both were in shot, because when they looked at each other when filmed, the resultant image showed the actors appearing to look past each other, particularly if they appeared on different films. Early directors sidestepped this latter problem by only shooting one actor at a time and cutting between them. Later directors worked out where to have the actors looking to create a natural shot. Each actor was required not to look at their fellow actor, but at a predetermined cue place instead.

Finally, the three individual films would jitter and weave slightly as the films moved through the projectors. This normal frame-to-frame movement is typically imperceptible to cinema audiences where only a single projector is in use. However, in Cinerama, this resulted in the center picture constantly moving slightly relative to each of the side pictures. The shifting displacements were perceivable at the two points where the center picture met the side pictures, resulting in what appeared to many viewers to be jittering vertical lines at one-third and two-thirds of the way across the screen as the two touching images constantly moved around relative to each other. Cinerama projectors used a device to slightly blur the join lines to make the jitter less noticeable. Future systems such as Circle-Vision 360° would correct for this by having masked areas between the screens. The jitters continued, but viewers were less aware of them with the adjoining pictures no longer so close together.

The impact these films had on the big screen cannot be assessed from television or video, or even from 'scope prints, which marry the three images together with the seams clearly visible. Because they were designed to be seen on a curved screen, the geometry looks distorted on television; someone walking from left to right appears to approach the camera at an angle, move away at an angle, and then repeat the process on the other side of the screen.

The first Cinerama film, This Is Cinerama, premiered on September 30, 1952, at the Broadway Theatre in New York City. The New York Times judged it to be front-page news. Notables attending included: New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey; violinist Fritz Kreisler; James A. Farley; Metropolitan Opera manager Rudolf Bing; NBC chairman David Sarnoff; CBS chairman William S. Paley; Broadway composer Richard Rodgers; and Hollywood mogul Louis B. Mayer.

Writing in The New York Times a few days after the system premiered, film critic Bosley Crowther wrote:

"Somewhat the same sensations that the audience in Koster and Bial's Music Hall must have felt on that night, years ago, when motion pictures were first publicly flashed on a large screen were probably felt by the people who witnessed the first public showing of Cinerama the other night... the shrill screams of the ladies and the pop-eyed amazement of the men when the huge screen was opened to its full size and a thrillingly realistic ride on a roller-coaster was pictured upon it, attested to the shock of the surprise. People sat back in spellbound wonder as the scenic program flowed across the screen. It was really as though most of them were seeing motion pictures for the first time.... the effect of Cinerama in this its initial display is frankly and exclusively "sensational," in the literal sense of that word. While observing that the system "may be hailed as providing a new and valid entertainment thrill."

Crowther expressed some skeptical reserve, saying "the very size and sweep of the Cinerama screen would seem to render it impractical for the story-telling techniques now employed in film.... It is hard to see how Cinerama can be employed for intimacy. But artists found ways to use the movie. They may well give us something brand-new here."

A technical review by Waldemar Kaempffert published in The New York Times on the same day hailed the system. He praised the stereophonic sound system and noted that "the fidelity of the sounds was irreproachable. Applause in La Scala sounded like the clapping of hands and not like pieces of wood slapped together". He noted, however that "There is nothing new about these stereophonic sound effects. The Bell Telephone Laboratories and Prof. Harold Burris-Meyer of Stevens Institute of Technology demonstrated the underlying principles years ago." Kaempffert also noted, "There is no question that Waller has made a notable advance in cinematography. But it must be said that at the sides of his gigantic screen there is some distortion more noticeable in some parts of the house than in others. The three projections were admirably blended, yet there were visible bands of demarcation on the screen."

Although existing theatres were adapted to show Cinerama films, in 1961 and 1962 the non-profit Cooper Foundation of Lincoln, Nebraska, designed and built three near-identical circular "super-Cinerama" theaters in Denver, Colorado; St. Louis Park, Minnesota (a Minneapolis suburb); and Omaha, Nebraska. They were considered the finest venues in which to view Cinerama films. The theaters were designed by architect Richard L. Crowther of Denver, a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects. The first such theater, the Cooper Theater, built in Denver, featured a 146-degree louvered screen (measuring 105 feet by 35 feet), 814 seats, courtesy lounges on the sides of the theatre for relaxation during intermission (including concessions and smoking facilities), and a ceiling which routed air and heating through small vent slots in order to inhibit noise from the building's ventilation equipment. It was demolished in 1994 to make way for a Barnes & Noble bookstore.

The second, also called the Cooper Theater, was built in St. Louis Park at 5755 Wayzata Boulevard. The last film presented there was Dances with Wolves in January 1991, and at that time the Cooper was considered the "flagship" in the Plitt theatre chain. Efforts were made to preserve the theatre, but at the time it did not qualify for national or state historical landmark status (as it was not more than fifty years old) nor were there local preservation laws. It was torn down in 1992. An office complex with a TGI Friday's on the west end of the property is there today.

The third super-Cinerama, the Indian Hills Theater, was built in Omaha, Nebraska. It closed on September 28, 2000 as a result of the bankruptcy of Carmike Cinemas and the final film presented was the rap music-drama Turn It Up. The theater was demolished on August 20, 2001.

A fourth, the Kachina Cinerama Theater, was built in Scottsdale, Arizona by Harry L. Nace Theatres on Scottsdale Road and opened on November 10, 1960. It seated 600 people. It later became a Harkins theater, then closed in 1989 to make way for the Scottsdale Galleria.

Venues outside the U.S. included the Regent Plaza cinema in Melbourne, Australia, which was adapted for Cinerama in 1960 to show This is Cinerama and Seven Wonders of the World. The Imperial Theatre in Montreal and the Glendale in Toronto were the Canadian homes for Cinerama.

This is Cinerama received its London premiere on September 30, 1954 at the Casino Cinerama Theatre, Old Compton Street, formerly a live theatre. The film ran for 16 months and was followed by the other three strip travelogues. How the West Was Won had its World Premiere at the Casino on November 1, 1962 and ran until April 1965 after which the Casino switched to 70mm single lens Cinerama.

London had two other three strip venues, making it the only city in the world with three Cinerama theatres. These were the Coliseum Cinerama, from July 1963 and the Royalty Cinerama from November 1963, like the Casino both converted live venues. The Coliseum played only one film in three strip (The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm) before switching to 70mm single lens from December 1963, and the Royalty had two runs of Brothers Grimm separated by a run of The Best of Cinerama before also switching to 70mm single lens in mid 1964.

These London venues were directly operated by Cinerama themselves, elsewhere in the UK three strip Cinerama venues were operated by the two main UK circuits, ABC at ABC Bristol Road, Birmingham and Coliseum, Glasgow, Rank at Gaumont, Birmingham and Queens, Newcastle and by independents at the Park Hall, Cardiff, Theatre Royal, Manchester and Abbey, Liverpool. Most of these conversions of existing cinemas came just as Cinerama was switching to single lens and thus had short lives as three strip venues before switching to 70mm.

Roman Cinerama Theater (now Isetann Cinerama Recto) at Quezon Boulevard in Recto, Manila and Nation Cinerama Theater in Araneta Center, Quezon City were the only Cinerama theaters built in the Philippines in the 1960s. Both theaters are now defunct as Roman Super Cinerama burned down in the late 1970s and became Isetann Cinerama Recto in 1988 while Nation Cinerama closed down in the early 1970s it is now Manhattan Parkview Residences built by Megaworld Corporation.

The last Cinerama theater built was the Southcenter Theatre in 1970, opening near the Southcenter Mall of Tukwila, Washington. It closed in 2001. Cinerama also purchased RKO-Stanley Warner (consisting of theaters formerly owned by Warner Brothers and RKO Pictures) in 1970. Stanley Warner Stanley Warner Corporation acquired 35% of the company as well as the exhibition, production and distribution rights to Cinerama in 1953 during production of Seven Wonders of the World which was planned as the follow up feature.

Related Collections

Additional Information

Certificates carry no value on any of today's financial indexes and no transfer of ownership is implied. All items offered are collectible in nature only. So, you can frame them, but you can't cash them in!

All of our pieces are original - we do not sell reproductions. If you ever find out that one of our pieces is not authentic, you may return it for a full refund of the purchase price and any associated shipping charges.